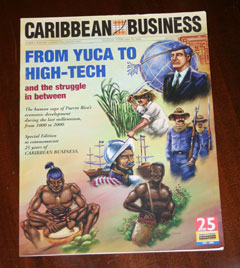

From Yuca to High Tech

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

- 1000: The Taíno civilization begins to flourish

- 1500: European conquest

- 1600: British for a while and other battles

- 1700: The age of pirates and privateers

- 1800: A dormant colony awakens

- 1900: Rough start with the U.S.

- 1910: The dawn of King Sugar

- 1920: The new regime — the Jones Act

- 1930: Desperate years

- 1940: Bread, land and liberty

- 1950: The turning point

- 1960: Turning toward modernity

- 1970: A new Puerto Rico

- 1975-2000: An economy matures

1930

Desperate years

To measure how far Puerto Rico has come today, it helps to look back to 1930, one of the bleakest moments of the century.

Certainly, progress had been made in the first three decades of U.S. rule. Anemia had been reduced and other diseases diminished. Roads had been built and, at least in the cities, most children now attended elementary schools, though most rural children did not.

But consider other indices of the health of Puerto Rico's economy and the well being of the people. In 1930, only one in four people had ever worn shoes. Four of five rural residents were landless and hunger was common among the poor.

As absentee owners in the United States controlled more and more of the sugar and tobacco production, Luis Muñoz Marín wrote in a 1929 article that Puerto Rico had become "a land of beggars and millionaires, of flattering statistics and distressing realities."

The dark prelude to the gloomy 1930s was the arrival on September 13, 1928, of the devastating San Felipe hurricane. Cutting a diagonal swath across the island, the hurricane left no part of Puerto Rico untouched. About 300 people were killed and 250,000 homes destroyed. A third of the sugar cane crop was lost and the fragile efforts to rebuild the coffee industry were stomped flat by San Felipe.

The situation in the coffee fields may have been the perfect symbol for Puerto Rico's desperate situation. The industry's long decline, hastened by the disruption of shipping to Europe during World War I, by San Felipe and by the Great Depression, actually meant that Puerto Rico had net imports of coffee from 1929 to 1934. At the end of the Spanish era, coffee had been a symbol of the island, but during the bleak beginning of the 1930s, Puerto Ricans couldn't even supply themselves with a morning cup of coffee.

The hurricane left Puerto Rico in the worst possible condition for facing the Great Depression, which began in 1929 and affected the entire world.

For much of the decade, per capita income declined. Sugar workers saw their pay drop, in some cases from 90 cents a day to 50 or 60 cents, even though some of the sugar companies remained quite profitable.

Unlike the situation in the United States, where both wages and many prices fell, prices in Puerto Rico actually rose for some imported goods, including food staples. In "Economic History of Puerto Rico," James L. Dietz cites some of the price increases that hit the poor hardest: 100 pounds of rice went from $2.40 to $4.10; 100 pounds of beans rose from $3.00 to $5.25; bacalao, or codfish, jumped from $19 to $28.

Using a physician's estimate of how much food various types of workers needed each day for basic nutrition, a study was done of purchasing power in Puerto Rico. It found that the weekly cost of a minimal diet was $3.19 per person in 1932. But in most industries, the average weekly wage was $3.00. Even before paying for housing or clothing, workers were falling behind.

The Depression and a second hurricane, San Ciprián, which hit in 1932 and killed another 225 people, did not spread their damage evenly, of course. Some sugar companies continued to produce impressive profits. Fajardo Sugar tripled its profits from 1931 to 1932 and, in the latter year, it was one of only seven corporations in the entire United States to post more than a minimal profit, Dietz notes.

A strike on the economy

During the era of King Sugar, the cane fields and the mills were periodically wracked by labor protests and strikes as the workers grew fed up with their conditions.

Most were isolated incidents involving one or two haciendas or maybe one central.

But the biggest strike of them all was also the last major clash between the workers and their employers.

The 1933-34 sugar strike laid bare some truths: the decline of the industry, the rift between the workers and the leaders of the unions that were supposed to represent them, and the impossibility of the political alliance between the Socialist Party and the Republican Union Party, which tied together labor leaders and some of the most reactionary landowners in Puerto Rico.

The strike began Dec. 6, 1933, the day before cane cutting was to begin, at the Central Coloso in Moca. Workers initially demanded weekly pay based on hours worked, not based on the amount of cane cut, which allowed the landowners to cheat them. By the end of the year, the strike had spread as far as Yabucoa and included Guánica, the most important area of all, and new demands were added.

Fields were idle and the sugar processing towns grew extremely tense. The government's Mediation and Conciliation Committee brokered an agreement and it was accepted by the union leadership and the sugar companies on Jan. 5, 1934. It was intended, for the first time ever, to apply uniform pay scales and work rules to the entire sugar industry islandwide.

The agreement offered cane cutters 90 cents a day, but the workers wanted $1.50. Seeing the agreement as little or no improvement, they defied their own leaders in the Free Federation of Workers and stayed out on strike. Former labor organizer Santiago Iglesias, now resident commissioner, also endorsed the settlement and was ignored by his former followers.

The strike spread from Fajardo to Maunabo to Dorado, with police occasionally attacking strikers. An estimated 50,000 sugar workers eventually took part.

With no leadership they could trust, the strikers called on nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos. To the chagrin of both the government and the spurned union leaders, Albizu drew huge crowds as he traveled from town to town urging the strikers to continue. Six thousand listened to his first speech in Guayama, and thousands more listened to him all around the coast.

Although Albizu Campos kept the strike going for a while, the impossibility of organizing workers scattered all over the island meant the labor protest eventually dwindled away. But it left several marks.

For one, it destroyed the coalition of the Socialists and the Republicans. The odd alliance was based on the Socialists wanting U.S. labor law protection and the Republicans wanting pro-business American rule. But the strike made clear that the alliance, which had won the 1932 election, had lasted only because the Socialist Party leadership, consisting of many of the same people who held office in the Free Federation of Workers, had abandoned the true concerns of the laborers.

"The strike showed the workers the ineffectiveness of their leaders," said historian Ivonne Acosta.

"It also raised Albizu Campos' profile on the island and increased the fears of the United States, because he was preaching violence," said Acosta, whose books include a collection of Campos' speeches and writings.

By 1934, the sugar industry's greatest days had passed and Albizu's prominence was about to rise further. The strike would be remembered as the last great attack by the workers on the industry that had made itself so rich and left them so poor.

§§§

One of the best portraits of life in Puerto Rico in the bleak times of 1930 was done by the Brookings Institution. It sent a team of researchers who traveled the entire island and looked under every rock to understand the island's current situations. The result, issued in 1930, was a thorough and voluminous report titled "Puerto Rico and its Problems."

The researchers examined every aspect of Puerto Rico's government and economy, but some of the most interesting insights were contained in the descriptions of the life lived by the typical Puerto Ricans of the era. Researchers visited the city neighborhoods and trekked up steep and slippery dirt paths to reach homes in the mountains that were far from the nearest road.

Especially in the countryside, they often encountered heartbreaking scenes of the poverty and suffering endured by the Puerto Rican jíbaros. "One may often see a boy carrying a baby in a coffin, going along the public highway, unaccompanied, wending his way to the public burial ground."

About three-fourths of the people still lived in the countryside, most of them owning no land and living rent-free in small huts, which meant the landowner could evict them if he wanted to.

"A great majority of the country people own neither the land that they till nor the crops they raise," the report stated.

In the country, the researchers found "line after line of mountain ridges dotted with peasant cabins that are accessible only by devious and precipitous trails."

The typical rural house was made of boards, thatch and bark, with a board floor raised on poles to let the rain flow underneath. They weathered quickly and were patched with tin cans, discarded boards or whatever else was at hand.

Most homes were no bigger than 20 feet by 20 feet, usually divided into two rooms. The kitchen was an outdoor lean-to. The only furniture usually found inside was a hammock for sleeping or perhaps a discarded oil can overturned to form a seat.

In this space, no bigger than a living room in a spacious home of today, lived an average of 7.7 people.

"Extreme cases are reported of 16, 18 and 20 people to a one-room shack," the Brookings researchers noted.

They estimated that the value of the possessions in a typical rural house was no more than $75, a monthly credit card payment for many Puerto Ricans of 70 years later.

Sugar workers made about $169 a year, while coffee or tobacco workers averaged about $135 a year. Of their wages, the jíbaros spent 94 percent on food, with rice, beans, coffee, sugar and bread together accounting for 49.4 percent of their food bill.

Landowners would keep the sharecroppers spread around their land so they could work different plots. So the jíbaros endured not only poverty, but also the depressing and unusual combination of living in a densely populated area while being isolated.

"They live dispersed in isolated individual families, although the country is crowded with people, and while the person wandering over the mountains is almost never beyond the sound of a human voice, there is practically no rural social organization," the report stated.

"Most of the dwellings hug mountain sides. They can only be reached on foot, over narrow paths. There the jíbaro, with his family, lives apart. He rarely goes to town."

Though they thought highly of education, few rural residents had attended much school themselves and often didn't send their children to school because they couldn't afford to buy them clothes. Though the Brookings researchers interviewed people throughout the mountains, they found just one rural man who owned a book, the story of Columbus' journeys. It had been lost in the San Felipe hurricane.

The researchers found two outstanding characteristics of the jíbaros: a fatalism and acceptance of their lot on one hand, and an unfailing courtesy and generosity on the other.

"Perhaps it is the widespread illness, perhaps it is the background of slavery and feudalism, perhaps it is the extreme poverty, perhaps the terrific impact of the periodic storms that carry all away with them and make human effort and ingenuity seem like naught, that explains the passive helplessness of the rural community.

"In spite of his fatalism, the jíbaro is kind, friendly and courteous, and hospitable to the last degree," the report stated.

One researcher recounted a story that illustrated the extreme hospitality of the jíbaro even under the most dark and depressing circumstances. The researcher had stopped to rest in front of a shack in the country and had begun talking to a middle-aged woman who lived there. After a few moments, he noticed that the body of a man who had recently died was lying in the small home, candles burning by his head.

"I am now poorer than ever," the woman said. "My husband is dead." Then, after pausing for a moment in her sadness, she turned to the Brookings researcher and said, "Won't you come in and rest? I will make you a cup of coffee."

§§§

The report found that the only truly urban part of the island was the San Juan-Bayamón-Río Piedras area. City dwellers were at least a little better off than the jíbaros in the mountains, if only because the pay was a little better and there were greater odds that more than one family member could find a little work.

Still, health problems plagued the people. Contaminated water was blamed for the leading cause of death, gastrointestinal illnesses, including typhoid. These diseases caused 21.8 percent of the deaths. The rate of tuberculosis was five times that in more densely populated New York and was the second most common killer.

Schools played an important role, especially in the country, where they were often the only center of activity in areas where there were no towns, just scattered laborers and sharecroppers. But another important development came in the form of roads built under the U.S. regime.

The Brookings Institution report's description of these roads shows the seeds of today's way of life in Puerto Rico at the end of the millennium, both good and bad, both traffic congestion and greater opportunity, both the ugliness of today's urban sprawl and the end of that era's stifling isolation.

"The paved road is the Great White Way of the Porto Rico countryman," the report stated. "Miles of almost continuous village have sprung up along the borders of these thoroughfares. The latter are thronged all day and part of the night with pedestrians, horseback riders, and above all automobile and bus travelers. In spite of the prevailing poverty, therefore, the travelled roads of Porto Rico present a cheerful and lively aspect compared with the relatively deserted highways in many Caribbean countries."

In a Puerto Rico so different from today's, the paved road was already seen as the changing force. In the bleakest of times, a visitor overwhelmed by the poverty could still see the cheerful and lively aspect of the Puerto Rican people finding a way to burst through.