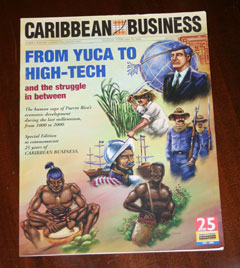

From Yuca to High Tech

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

- 1000: The Taíno civilization begins to flourish

- 1500: European conquest

- 1600: British for a while and other battles

- 1700: The age of pirates and privateers

- 1800: A dormant colony awakens

- 1900: Rough start with the U.S.

- 1910: The dawn of King Sugar

- 1920: The new regime — the Jones Act

- 1930: Desperate years

- 1940: Bread, land and liberty

- 1950: The turning point

- 1960: Turning toward modernity

- 1970: A new Puerto Rico

- 1975-2000: An economy matures

1700

The age of pirates and privateers

"The new century began with misery, low population and commercial smuggling; where the previous century left off," Gilberto R. Cabrera wrote of the year 1700 in his history of Puerto Rico.

Changes were coming, but they would take nearly a century to gain momentum.

In 1700, Puerto Rico's population was still just 7,400, though at least it was growing. During the first half of the century, a decrease in emigration and slightly larger numbers of newcomers caused the population to increase by better than 5 percent a year.

Still, most of the island remained an untouched jungle, and the population easily cleaved into two separate groups. There was the military enclave of San Juan, now a walled city protected by strong fortifications. The people of the other settlements on the island lived a pioneer existence, distant from the rule of the colonial governor and the Spanish crown, and forced by necessity to deal with both the allies and the declared enemies of those authorities just to meet their basic needs.

By 1700, dealing in contraband was the normal way of life and primary mode of commerce in Puerto Rico. By one estimate, the illegal trade outweighed the legal trade by a factor of 10 to 1. The combination of restrictive laws and lack of attention from Spain left no other alternative.

In the mid-1600s, a colonial governor complained that not one officially registered ship from Spain had arrived in the port at San Juan in 11 years. The residents of the capital at least had the proceeds of the situado to support the troops and the bureaucracy, though it often came late and frequently wasn't even enough to keep the soldiers in uniforms.

The only thing the residents of the rest of the island had was the freedom to buy and sell as best they could, with anyone, not just Seville, as Spanish decrees required. Not that smuggling didn't take place in San Juan. It did, but the colonial authorities got their cut.

On the distant farms and in the small settlements, the laws on trading were ignored, both by convenience and by necessity. Spain was doing nothing to help those isolated communities, so the pioneers felt no need to follow Spain's impossible strictures.

French, Dutch and even British ships would anchor in the island's coves and bays far from the sole official port of San Juan and unload their wares, perhaps taking on hides, animal fat or locally grown fruits and vegetables in exchange.

While this illegal trade continued with impunity most of the time, the colonial authorities would occasionally make an attempt to stop the smuggling.

In 1702, a Dutch ship was stopped off the west coast of Puerto Rico and found to be full of locally grown fruit it had just picked up from San Germán. Colonial Governor Gabriel Gutiérrez y Rivas ordered an investigation, but all the San Germán residents professed ignorance, while the crew of the seized ship blamed all of San Germán.

Gutiérrez y Rivas fined every family in San Germán, a ruling the locals decided to protest, as they had done before, to the authorities in Santo Domingo. This only angered the Puerto Rican governor even more, the thought of his own subjects going to other authorities to protest his decisions. He called the two top officials of San Germán to San Juan, and as soon as they arrived he had them thrown in jail.

When other city officials went to Santo Domingo again to protest, they too were imprisoned, at the request of Gutiérrez y Rivas. As a result, for a time in the early part of the century, the entire municipal government of San Germán was in jail in San Juan and Santo Domingo.

Such threats of punishment did nothing to deter dealing in contraband elsewhere on the island. The unmet needs of the people ensured that.

While the British possessions in the West Indies were becoming the most valuable of all, Spain did almost nothing to develop agriculture in Puerto Rico. In the countryside, farms subsisted as best they could with limited equipment and primitive methods.

The British were developing major plantations on their islands, growing sugar cane in Jamaica, for example. But Puerto Rico, the same size as Jamaica, was producing less sugar in the mid-1700s than it had in the mid-1500s. Spain appeared neither able nor interested in developing Puerto Rico. It just wanted a well fortified outpost to help guard its shipping from more lucrative possessions.

But even that was difficult to maintain. The soldiers stationed in San Juan were usually dressed in rags. They often received food only due to the patience of landowners who brought in local fruits and crops and were willing to wait indefinitely to be paid. There was never enough money nor manpower.

Miguel Henríquez: The first Puerto Rican entrepreneur?

The idea that a Puerto Rico-born, mixed-race shoemaker could rise to be one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in early-1700s San Juan seems unlikely. Yet he did.

Maybe the most attention-grabbing success story during the first centuries of Spanish rule was that of Miguel Henríquez.

Henríquez first made his name at sea in the constant battles among would-be invaders, pirates and privateers trying to loot both legal and illegal trade. King Felipe V made Henríquez a captain in 1713 and awarded him the Medalla de la Real Efigie.

Henríquez further proved himself in the battle to kick the British out of Vieques in 1718, a role that earned him a different title from the British: the "grand arch villain."

"He was the most important man on the island in the first half of the 18th century," according to historian Luis M Díaz Soler.

By playing both sides of the smuggling game, Henríquez amassed a fortune, building a fleet of 25 ships. While he was one of the principal dealers in contraband, he also won an appointment as a privateer from the Spanish king, giving him license to intercept other smugglers' shipments while he continued with his own. He gave so much money to the church that its leadership promised to say mass for his soul and his mother's "forever."

A local-born mulatto with wealth and power was a natural magnet for enemies, however. Many in the white elite from Spain wanted to destroy him, if only due to envy, and they arranged for Henríquez to be charged with smuggling.

Henríquez fled with much of his fortune to the protective arms of the church, where his devotion to the Catholic faith and his generous gifts over the years had earned him strong allies. Although the charges against him were eventually dropped, he never regained the prestige he once had. He eventually died in the convent where he had taken refuge.

If nothing else, Miguel Henríquez, who could have quietly made shoes his entire life, proved what a man with ambition could do, even with the curse of racial prejudice working against him.

It is clearly the first instance of a local Puerto Rican who started out poor, ventured out as an entreprenuer and built a big, dominant business in his industry. Today, there are many like him. In the early 1700s, there was only one.

In that scenario, the Spanish crown turned to local talent to help guard the coasts of Puerto Rico. Thus arose the importance of the corsos, or privateers. It was the age of pirates and privateers, and often it was hard to tell the difference between the former, who obeyed no laws, and the latter, who supposedly drew their authority from the crown and were loyal to it in return.

As historian Arturo Morales Carrión noted, however, "An abyss existed between theory and practice." The Spanish crown handed out patentes de corso, or privateer commissions, with the idea of enlisting ambitious locals in the mission of protecting Spain's trade. Supposedly, the privateers would intercept illegal shipments into Spain's colonies, such as Puerto Rico, and also protect the coast from foes.

In reality, most of the privateers were smugglers themselves, and they used their blessing from the king to thwart rivals and loot ships mostly as they pleased.

For a young man of modest means born in the colony, a commission as a privateer meant a risky life, but one of adventure and possible riches and fame. The other alternative was usually to practice a humble trade in San Juan or to toil on one of the farms in the countryside that belonged to elite and supplied the city with food.

At best, he might sit on a horse and oversee some slaves hacking sugar cane or picking fruit on an isolated farm. Or he could be at sea, looting treasure-filled ships, stealing what he wanted, and fighting the despised British.

While San Juan had its fortifications, troops and privateers, the outpost settlements were on their own when it came to protection, as well as commerce. Power struggles in Europe inevitably reached into the Caribbean.

The rivalry between Britain and Spain grew in the first years of the century due to the War of Spanish Succession. France became closely allied with Spain, balanced by a British-Austrian alliance which also included the Dutch.

Attacks from Spain's enemies periodically threatened Puerto Rico's coasts. A band of British sailors landed near Arecibo in 1702. The Spanish defenders pretended to flee into a forest, but then hid and ambushed the British when they followed, killing the majority of the invaders.

Similarly small-scale and unsuccessful incursions were made by the British in 1702 in Loíza, and the following year, on the south coast, by the Dutch.

Periodically under attack and virtually abandoned by Spain, Puerto Rico in 1700, nearly two centuries after the first settlement was founded at Caparra, was still an outpost populated by a relative handful of settlers. In some ways, little had changed.

Changes were coming, but it would take a new regime in Spain and nearly another century before Puerto Rico would finally come alive.