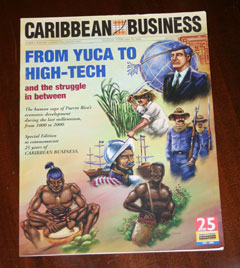

From Yuca to High Tech

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

- 1000: The Taíno civilization begins to flourish

- 1500: European conquest

- 1600: British for a while and other battles

- 1700: The age of pirates and privateers

- 1800: A dormant colony awakens

- 1900: Rough start with the U.S.

- 1910: The dawn of King Sugar

- 1920: The new regime — the Jones Act

- 1930: Desperate years

- 1940: Bread, land and liberty

- 1950: The turning point

- 1960: Turning toward modernity

- 1970: A new Puerto Rico

- 1975-2000: An economy matures

1000

The Taíno civilization begins to flourish

One thousand years ago along the coast of what we now call Puerto Rico, a woman rose eagerly from her hammock as the first rays of sunlight pierced the loosely slatted bamboo walls of her little, round bohio.

Her heart was light because today she would climb the hill above the growing village where she lived to the special pool in the stream where she always found the best flat rocks, the perfect materials she needed for the amulets she made for herself and for others to wear.

One of the nitaínos, the village leaders who organized the harvesting of yuca and the planning of festivals, suggested she make some of her sought-after adornments, because a celebration was in the works.

Some of the others liked to make their amulets of shell or wood, which were easier to work with, the young woman admitted. But she liked the permanence of stone, the way it felt like it would last forever, like the earth itself, like her mountainous green island, Boriquén. And she knew where to find the best, flat stones, which she would then spend many hours polishing. So she set off between the clusters of bohios for the stream.

As soon as she began climbing the hill, she stopped for a long drink of water and for a view of the fields below. The yuca field grew larger every year, and never failed to feed the growing village. The nitaínos made sure the fields were left fallow some years, to let them recover before another crop was planted. The fields looked lumpy, from her distance.

Her people, who would be known centuries later as Taínos, built mounds of dirt 10 feet in diameter, planting the yuca in terraces on each mound. They fertilized the dirt with ashes and let trees grow amongst the fields to provide partial shade.

Even at this early hour, she could see women moving among the mounds, pulling from the ground the yuca that would be pounded to paste and made into their daily bread. There were no men in the fields. Farming was women's work, as was the making of the ceramic, wood, stone and shell baubles that was her mission for the day.

From her spot on the hillside, it was easy to see the result of the agricultural knowledge on display below. Just as the yuca field now spread for dozens of acres, the village itself was growing. She could see more than a hundred bohios now scattered around the batey, which would be the center of activity on the day of celebrations the nitaínos had promised would come soon. It was the yuca that allowed the village to grow.

Her mother's mother, now long since gone on to Coabay to spend the nights celebrating and roaming the earth with the spirits of her other relatives who had died, had told her when she was a little child of a time when the village was barely more than one extended family. Strangers were a rare sight, then.

But with the steady supply of food ensured, the village had grown, and men came in their canoes from other villages, sometimes to trade valuable belongings such as thread made from wild cotton or baskets woven from fibers. She could see men on the beach, making repairs to their nets or maybe checking the hooks and darts they used for fishing. Her own husband would be there among them, ready to go to sea again in the canoe he had spent hours forging from a tree trunk with the force of his own hands and fire. She hoped maybe he would catch a sea turtle today. She loved the taste of it.

Realizing she had daydreamed too long, she turned and hurried up the little path by the stream. Except for the little settlement she called home, and the blue sea spreading off to the horizon, everything she could see of the land was green, trees and vines and plants of a thousand hues barely varying the same theme. So much green everywhere. Sometimes she felt as if her eyes ached from the richness of the color.

It was a beautiful island, her Boriquén. No doubt with some flat stones that could be polished to a special kind of beauty, she thought, as she arrived at a secret pool in the stream...

§§§

In the strictest sense, all of the above is, of course, fiction. There is no detailed written record of Taíno life, except for some accounts by the first Europeans who came to Puerto Rico and observed the indigenous people. But thanks to the painstaking work of archaeologists, we do know enough to imagine such a day, and the life of such a village, at the last turn of the millennium.

Unlike this millennium's hoopla, the year 1000 passed unnoticed in Puerto Rico. The people who then populated the island had never heard of Jesus Christ, much less set their calendars by his birth. Certainly, nobody was worried about "Y1K" issues.

But it was an important time in Puerto Rico's history just the same. Archaeologists date the beginning of what we call Taíno culture to about this time period. The first evidence of human habitation of Puerto Rico dates back about 2,000 to 3,000 years. During the Archaic phase, as it is called, the island was populated by people who did not know agriculture or make pottery.

Centuries later, Arawak people from what is now Venezuela migrated up the Caribbean chain of islands, many of them settling in Puerto Rico. Archaeologists divide the development of their society into phases: the Igneri or Salaloides, the Ostiones and the Santa Elena cultures.

By the end of the first millennium, the Taíno culture was emerging in the Greater Antilles. The beginning of Taíno times is not marked by sharp changes in the way people lived or by a single date or special occurrence. Rather, it was the sum of numerous changes that marked another advance in the culture.

The key, as in the development of all advanced cultures, was improvement in agriculture. Yuca was the staple, supplemented by a few lesser crops and what the men could hunt from the forests and, mostly, from the sea. Just as cultivation of corn led to the Mayan civilization, and potatoes supported the Incan empire, yuca fueled the development of Taíno society.

As the Taínos became more adept at growing yuca, the steady and reliable food supply allowed villages to develop where before only small clans or tribes could band together. Divisions of labor grew, societal structures became more complex, and entire regions were bound together with political structures. The relative wealth of a steady food supply also allowed the Taínos the luxury of developing a way of life rich in symbolism and religious beliefs.

"When ceremonialism occurs in any society, it indicates that one sector of society is receiving goods they are not producing," said archaeologist Argamenon Gus Pantel.

The division of labor created the leadership class whose functions were both political and religious. The batey was the site of ceremonial events, but it was likely used for other activities, especially when traders from other villages arrived, some archaeologists believe. Some 200 of these traditional plazas, lined with standing stones, have been found all around Puerto Rico. The building of the plazas was just one of many manifestations of the emergence of what is today classified as Taíno culture.

Boriquén: Bridge to the Americas?

Archaeological evidence suggests that Puerto Rico was a hub of human activity in the Caribbean during the era of the Taíno culture.

Just as Puerto Rico is a commercial center today, between the North and South American land masses, it was also a way station in the times when people traveled in small wooden boats carved from tree trunks.

Humans came to Puerto Rico centuries before the Taíno civilization developed. Whether these pre-agricultural, pre-ceramic peoples came from North, Central or South America is unknown for certain, but it's likely that travelers came from two or all three of those points. Much later, natives of the Orinoco Valley in what is now Venezuela came to the islands, including Puerto Rico, and developed what became the Taíno culture.

A key piece of evidence about Puerto Rico's role in the Taíno society is the presence of some 200 plazas that have been found on the island.

"From a worldwide archaeological and anthropological viewpoint, when a phenomenon like this occurs, normally there is a similar distribution that occurs in the geographical area," said archaeologist Argamenon Gus Pantel. "One would anticipate that in the Lesser Antilles, for example, you would encounter fewer plazas, or smaller plazas, and in the Greater Antilles, Cuba, Jamaica and the others, more plazas and bigger plazas. But that doesn't happen."

Why? One theory is that Puerto Rico was an important center in the Taíno civilization in the Caribbean, more important that the other, larger islands.

Nearly a millennium ago, Puerto Rico was already a hub of activity in the Caribbean.

§§§

These changes were just beginning at the last turn of the millennium and the Taíno culture would continue to develop over the next five centuries. Settlements grew larger and trade between villages, even between islands, increased. They had no currency, so Taínos bartered what they had for what they wanted.

Some of the first Europeans to arrive saw Taínos trading a beautiful gem for a simple needle and concluded the Taínos didn't understand commerce. That view was attacked by Labor Gómez Acevedo and Manuel Ballesteros Gaibrois, Puerto Rican and Spanish university professors, respectively, in their book, "Culturas Indígenas de Puerto Rico."

The Taínos "knew perfectly well the relative value of the merchandise, and in their daily business they sought what they didn't have in exchange for what they did have," they write. "Those who didn't understand this value were the Europeans, who appeared ignorant of the law of supply and demand, that a needle or an item they did not know how to make could easily compare to an object they made themselves and knew they could make again. All of this in a framework of a world in which 'value added' by labor had never been expressed."

Like any resident of the island today, the Taínos knew shipping. They built canoes of all sizes, some using sails made from wild cotton, some big enough to accommodate 45 people. The canoes were made from tree trunks, hollowed out with stone tools and fire, and treated again with fire to make them durable.

The first Europeans who saw the Taíno vessels said they were remarkably stable, though they were small for open ocean voyages. Still, those handmade boats were what brought humans to Puerto Rico many centuries before Europeans arrived and served as a means of travel and trade for five centuries of Taíno culture.

The emergence of the Taíno culture brought to Puerto Rico for the first time many of the same concepts that still govern our civilization today. Where bands of seminomadic hunters and gatherers had spent their lives in the daily search for food, the Taínos built a society around permanent settlements, an organized division of labor and political structures.

A person of that age perhaps earned a living by tending to yuca or fishing, and today we may earn our salaries by being a banker or a bus driver. But we have only elaborated these economic structures.

One thousand years ago, the Taínos were the first Puerto Ricans to invent them.